I still remember clearly that feeling from 12 years ago, as I was driving on I-25 through Denver. Easter was on the horizon, and I wanted to do something about it. My church didn’t really observe liturgical seasons, and I knew nothing about Orthodox Christianity. (Isn’t that an Eastern European form of Catholicism?)

Yet I still had a strong urge to observe Lent in some way. The problem was, I didn’t know how or what to do.

The traffic wasn’t too bad as I headed north in the middle of the day, and I was in a contemplative mood. I decided that I would mark this unmarked season by listening to Michael Card’s three-CD trilogy from 1988, The Life, about the life and ministry of Jesus. (I still highly recommend Card’s music for its lyrical depth and biblical focus.)

I then decided that for Lent I would listen only to Christian music until Easter, to help keep my thoughts focused on Christ. I would read a Gospel chapter every day. I think I also gave up chocolate for a while, but that ascesis proved too difficult for me to sustain for forty days.

Notice that the terms I, me, and my occured seven times in the previous paragraph. I made these decisions while driving alone, with no guidance, no church tradition, and no community support.

Yet somehow my heart knew that celebrating Easter should be more than a day-long event—church in the morning, baked ham for lunch, and an Easter egg hunt. It seemed that Easter required some spiritual preparation, but my religious surroundings barely acknowledged this need. I still recall the year my children’s Evangelical Christian high school scheduled a half-day of classes on Good Friday and a drama practice on Holy Saturday. None of the other parents had a problem with this, because Easter was considered a stand-alone day, not the culmination of a larger season.

Not-So-Great Lent: A Matter of Individual Conscience

My desire to “do” Lent was not unusual. This human need to mark times and seasons is, I believe, God-given, and it was built into the worship of ancient Israel, with its calendar of feasts, fasts, and festivals.

But in the West, the Church has splintered since the Protestant Reformation, with no Capital-T Tradition to unite us. Anglicans, Episcopalians, Lutherans, and Methodists still observe Lent, but the marking of seasons in the life of faith has, in some quarters, been jettisoned entirely. Baptists and Pentecostals don’t observe Lent at all. With some Christian groups, this rejection of feasts and fasts stems from a very literal biblicism (“If it’s not in the Bible, it’s not important”), but often it is a rejection of anything that looks, smells, sounds, or feels Roman Catholic.

And among those Protestants who embrace Lent, “the extent to which they alter their day-to-day lives varies greatly and is mostly a question of individual conscience. These disciplines include restricting food, giving up luxuries (including, in the 21st century, social media), and engaging in charitable work” [from the Daily Beast article, “The Greatest Myths about Lent”].

That whole “individual conscience” thing explains my sense of confusion over how to approach the weeks leading up to Easter. The churches that our family attended had no ecclesiastical calendar and would come up with their own observances, which varied from year to year—much like trying on the latest fashions.

In our Evangelical milieu, innovation was valued—a new choir musical for Easter, a special service of silence added to the Holy Week calendar, an all-church fast declared for a time of difficulty, a new approach to Scripture reading during Advent. In one church we attended, tradition and continuity were viewed with suspicion, responsible for “quenching the Spirit.” That church split and disbanded many years ago.

But on my lonely freeway drive, I wasn’t thinking about anything as lofty as ecclesiology or systemic problems in Western Christianity. I just knew that I wanted to participate in something, and to participate in community. I wanted “us,” not “me.” And I would have to wait many weeks for Good Friday in order to experience that sense of community on a day other than Sunday.

Of Ashes and Repentance

In the West, when Lent is observed at all, it begins on Ash Wednesday. Although individual churches practice the “imposition of ashes” differently, typically a priest or pastor will mark the sign of the cross on a person’s forehead with a mixture of ashes and oil or water and say, “Remember that thou art dust, and to dust thou shalt return” (Genesis 3:19), followed by the admonition, “Turn away from sin and be faithful to the Gospel” (Mark 1:15).

The cross of ashes on the forehead (which, by the way, is not an Eastern Orthodox practice*) is a beautiful token of repentance and a reminder of our mortality. It is also a powerful ceremony precisely because it is a communal one: the congregation gathers with intentionality to worship together, to experience together this physical reminder of our inner state, and to commit as a community to a season of repentance.

Unfortunately, the community-wide focus often stops there, to appear again during the latter part of Holy Week or perhaps only with the Easter service.

Do-It-Yourself Lent

From Ash Wednesday forward, the observance of Lent in the West has become individualized. A casual website search of Lenten-friendly churches shows a basic agreement on the meaning of Lent: it is a 40-day time of repentance, self-reflection, and contemplation of Jesus’ sacrifice on the Cross, culminating with His glorious Resurrection on Easter Sunday.

But what about the actual practice? What does one do during this season? The “us” of Ash Wednesday often segues to the experience of traveling the Lenten journey alone—yet another example of the Protestant “me and Jesus” mentality. The liturgical churches offer a basic structure for Lent, but parishioners flesh it out on their own.

According to one Anglican pastor’s website, fasting on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday is traditional, along with practicing abstinence from meat on the other Fridays of Lent (an echo of the modern Roman Catholic practice). But “giving up something” for Lent is a matter of individual choice.

A Methodist church’s website offers a similar approach. The ancient disciplines of prayer, fasting, and almsgiving (or service) are mentioned, but without specifics. Increased private prayer is encouraged, but corporate prayer services are not part of the mix. Parishioners are encouraged to fast, but they define their fasts individually (giving up television, coffee, candy, cigarettes, social media). Service is also a matter of individual choice, such as performing extra volunteer work or collecting canned goods for a food pantry.

All of these private practices are beneficial, and of course as Orthodox people we need to make personal decisions regarding our own ascetic endeavors—preferably under priestly guidance. But our individual acts of prayer, fasting, and almsgiving, performed in secret before God, are done in the context of corporate fasting, corporate prayer services, and corporate encouragement to give sacrificially. Great Lent is not a DIY project.

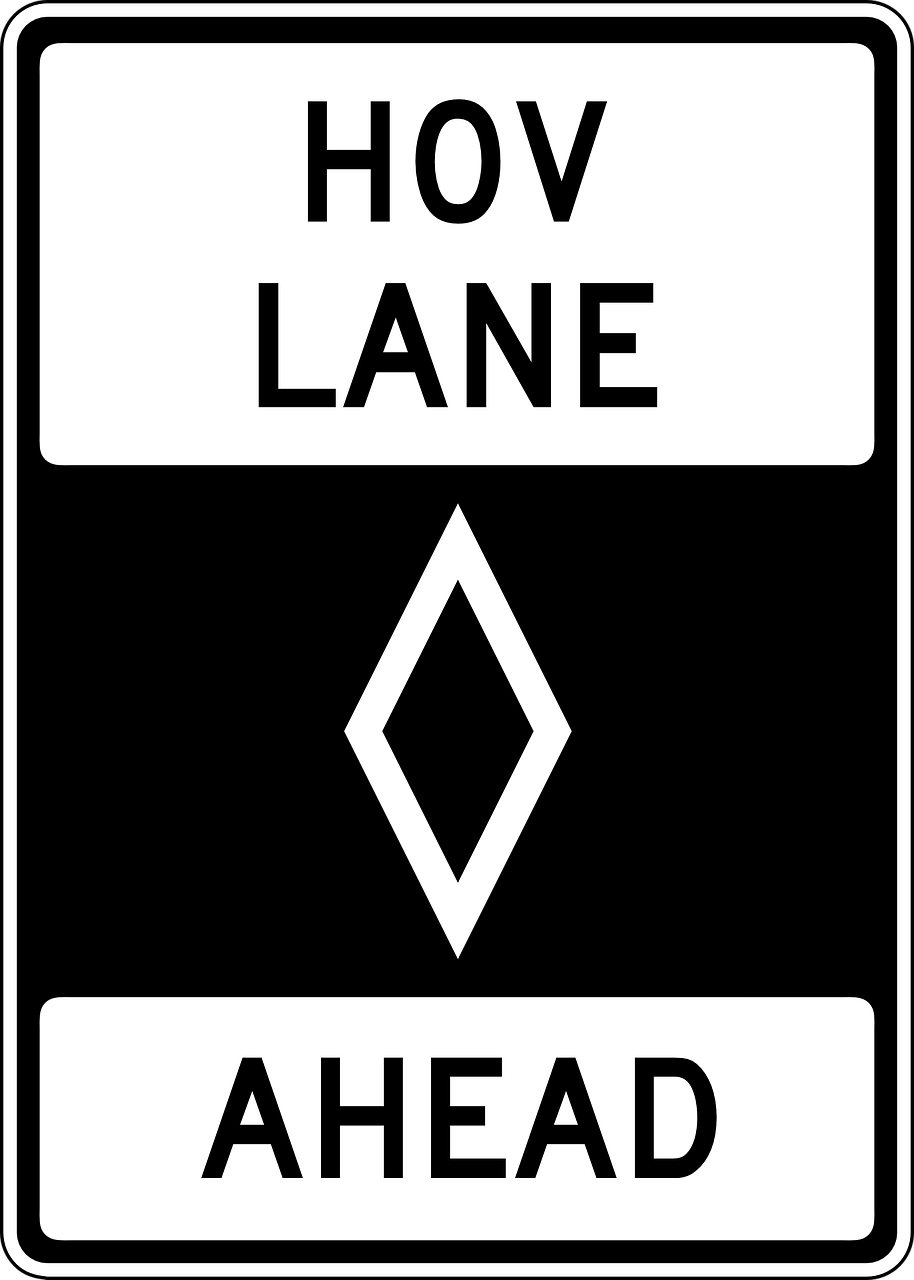

In the Orthodox Church, we travel the Lenten road together. My parish is like a bus full of penitents in the High Occupancy Vehicle lane, surrounded by the other buses in the caravan of the Church. We travel together, in the same direction, on our journey to Pascha.

Yesterday my husband and I drove north on I-25 to visit our son and daughter-in-law. We passed the same industrial areas, fast-food restaurants, and car dealerships that I passed 12 years ago. The traffic was worse than it used to be, but I no longer wondered what to do for Great Lent.

I know that I will need to clear my schedule to attend extra services with my fellow parishioners. I have already cleared my pantry and freezer in preparation for our corporate fast. I have flipped through my best crowd-pleasing, vegan recipes to find yummy dishes to share during our parish-wide Lenten meals on Wednesdays. I will participate in pan-Orthodox giving opportunities for international and local ministries.

Prayer, fasting, and almsgiving: these are the three areas of focus during this season of repentance. I will likely experience discouragement and miss the mark in every area.

But I won’t be traveling the road of Great Lent alone.

* Although Orthodox Christians of the Western Rite celebrate Ash Wednesday, the Eastern Church does not, following Jesus’ admonition, “when you fast, anoint your head and wash your face, so that you do not appear to men to be fasting, but to your Father who is in the secret place; and your Father who sees in secret will reward you openly” (Matt. 6:17–18). For us, the season of Lent begins on Forgiveness Sunday, during the evening service of Forgiveness Vespers. Instead of ashes, we exchange kisses of forgiveness.

My ROCOR Western Rite church does not observe Ash Wednesday for reasons you stated the larger Orthodox Church does not.

Have a blessed Lent!

Thanks, and good strength to you!

“Although Orthodox Christians of the Western Rite celebrate Ash Wednesday, the Eastern Church does not, following Jesus’ admonition, “when you fast, anoint your head and wash your face…”

I didn’t realize we were supposed to literally follow this admonition. How do I anoint my head exactly? Just smear some olive oil on my face, then wash it off?

I meant following Jesus’ admonition to appear clean and well groomed, rather than revealing our fasting by a mournful appearance. For example, in several places in the Old Testament, people in mourning tore their clothes and put on sackcloth, sometimes with ashes (Esther 4). Jesus’ overall point is for us to fast and pray in secret. We don’t have a tradition of anointing our heads, except perhaps for the sacrament of Holy Unction. 🙂

You can ask your priest for some holy/blessed oil, they usually have a large supply. He will provide you a vial to take home and you may anoint your own forehead daily upon waking, nightly before bed, any time you pray. etc. Most parishes also often have stashes of oils sitting with one or more of the icons that you can use in church. We are also often anointed in church during feast days or special celebrations. Recently, we received the wonder-working icon of St. Anna in our church and we were appointed by the Archbishop after venerating the icon.