Back in the late ’90s a friend of mine related a conversation with her father, an old-school Baptist who was bemoaning his church’s musical transition from traditional Protestant hymns with keyboard accompaniment to a band on stage leading the congregation in modern praise choruses.

“Seven–ten songs,” he called them. “Seven words, and ya sing ’em ten times.”

We laughed together, and the following Sunday at my nondenominational church we sang a song that was popular at the time. The lyrics said: “Open the eyes of my heart, Lord / Open the eyes of my heart / I want to see You / I want to see You.”

With my fingers I quietly counted the words of that first line: “Open the eyes of my heart, Lord”—seven. And we sang them over and over. I had to cover my mouth so that no one would see me laughing. I didn’t check to see if we actually repeated the chorus ten times, but . . . point taken.

The musical content of my final decade in the Protestant world was radically different from anything I’ve experienced in the Orthodox Church. Besides the obvious absence of drums and electric bass in the choir loft, our Orthodox hymns are in a different category than these praise choruses. Praising God is an important function of worship —just flip through the Psalms for proof—but music in the Orthodox Church also provides an opportunity for the Church to teach us and shape our thoughts.

We can see this teaching function in the singing of the antiphons. In the first episode of our Liturgy Quick-Start Guide we looked at sections one through three of the Divine Liturgy: the Great Litany and the first two antiphons. Today we’ll examine section 4, which includes a lot of musical theology with the third antiphon and the Little Entrance (or “Small Entrance”) of the Gospel Book.

Section 4: The Third Antiphon

The musical selections change according to the festal season, but they include a brief hymn called a troparion to commemorate a feast day, often paired with a kontakion, which explains the meaning of the feast. (Someday I’ll remember which is which.) In Let Us Attend! A Journey through the Orthodox Divine Liturgy, Fr. Lawrence Farley writes, “In listening intently to the troparia, we learn what the Church teaches about the Lord, the Mother of God, the saints, and the great saving events of the faith” (p. 30).

In Russian Orthodox churches, people also chant the Beatitudes together, but Greek churches no longer do this. I’m not sure why, and personally I consider this a loss. Memorizing and singing the Beatitudes is a wonderful way to tuck Jesus’ words into our heart and minds.

Each individual parish also sings a hymn about the saint to whom their temple is dedicated, and on Sundays, the day of Christ’s Resurrection, the liturgy always includes a resurrectional hymn. If you attend a weekday liturgy, you might experience a vague sense that something is different. This could be because you’re missing the hymn about the Resurrection, even if you aren’t consciously aware of it.

![]()

Although the teaching function of hymns unfortunately has been largely lost in many Protestant churches and replaced with those repetitive praise choruses, historically the instructional focus of hymns has been valued for centuries throughout all branches of Christendom.

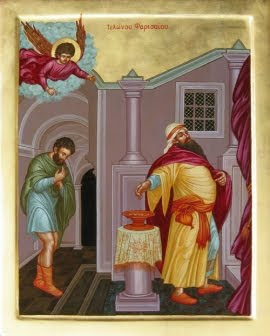

For example, in an early version of this series on my blog, I was writing about the antiphons just after the Sunday of the Publican and the Pharisee (from Jesus’ parable in Luke 18:9-14), which inaugurates the three-week Triodion period every year before Great Lent. One of the hymns on that day includes the words, “Eternal with the Father and the Spirit is the Word, Who of a Virgin was begotten for our salvation.” This one short line clearly proclaims a Trinitarian Faith and the Virgin birth of Jesus Christ.

Next, the words of the kontakion admonish us: “Let us flee from the boasting of the Pharisee and learn through our own sighs of sorrow the humility of the Publican. Let us cry out to the Savior, ‘Have mercy on us, for through You alone are we reconciled.’”

These two short hymns give us a lot of food for thought, and during each Liturgy the Church feeds us a rotating banquet of rich theology. Nothing here addresses my feelings. Instead, the Church confronts my ego, on this particular Sunday reminding me that any act of self-denial during Lent is worthless without a humble heart. The repentant tax collector is my example, not the prideful religious official.

I’ll admit, Orthodox hymns often aren’t very hummable. They certainly don’t have a good beat. Yet poetry is in the music of the Church, and so is beauty—and challenge. The hymns exhort us to a deeper life of faith, proclaim spiritual truths, and offer loving honor for our parishes’ patron saints and other godly men and women who have traveled this path before us.

St. John of Kronstadt advises us,

Revere every work, every thought of the Word of God, of the writings of the Holy Fathers, and amongst them, the various prayers and hymns which we hear in church or which we read at home, because they are all the breathing and words of the Holy Spirit.

The words of the Church’s hymns are meat, not milk. Musically and lyrically, and with the help of the Holy Spirit, the antiphons help prepare our hearts and minds for the next section of the Divine Liturgy, the readings from the Word of God.

Part 5: The Little Entrance and Scripture Readings

While we sing hymns, the priest takes the Gospel Book off the altar table, circles it, and enters the nave, preceded by acolytes bearing candles. This procession is called the “Little Entrance.”

The Gospels are accorded this parade, including an honor guard of lights, because the written Word reveals to us the living Word, Jesus Christ. The Gospels proclaim Jesus as Light of the World and call us to shine His light in our lives.

The deacon cries, “Wisdom! Let us attend!” or “Let us stand aright!” Crossing ourselves and bowing, we respond in song:

Come let us worship and bow down to Christ, the Son of God.

Save us, O Son of God, who is risen from the dead. We sing to you, Alleluia.

The Trisagion Hymn

Following this response, we join the saints and angels in another beautiful song of worship, the Trisagion Hymn: “Holy God, Holy Mighty, Holy Immortal, have mercy on us.”

This is about as close to a praise chorus as the Orthodox Church gets. I find the Trisagion Hymn and “Come Let Us Worship” to be very melodic and hummable, and easier for me to recall during the week. The Thrice-Holy Hymn is definitely not happy-clappy; it is a truly sacred moment in the course of our liturgical journey. In his book Living the Liturgy, Fr. Stanley Harakas comments that these words:

are not informative statements about God, but rather expressions of the awed reverence of a sinful creature as he stands before the Completely Other, The Transcendent, the All-powerful and Eternal Being whom he calls God. ‘Holy God’ we whisper in awe and reverence; ‘Holy Mighty One’ we address Him, fully cognizant of our own weakness; ‘Holy Immortal,’ we mortal time-bound beings name the Everlasting One. And then humbly, with His greatness and our smallness evident before us, we petition, “Have Mercy on us!”

This is one of the most ancient hymns of the Church and is deeply Trinitarian: each phrase—holy God, holy Mighty, and holy Immortal—addresses Father, Son, and Holy Spirit. It is the hymn of the angels, adapted from the sixth chapter of Isaiah: God, high and lifted up, sits on His throne in the temple while the angels surround Him, singing, “Holy, holy, holy, Lord of Hosts! The whole earth is full of Your glory!”

The Blessing of Peace

Next the celebrant greets the people with, “Peace be with you all!” We respond, “And with your spirit!” This blessing of peace occurs several times throughout the service, and like the Small Litany, it can occasionally give newcomers a sense of déjà vu. Yes, you did hear this before. Yes, you will hear it again.

But these words are more than a religious nicety; we need this peace and the reminder that Christ is with us, because we cannot listen and discern with troubled, distracted hearts and minds. The peace that the priest offers is not something he conjures within himself; it is the peace of Christ.

This fourth section ends with an abbreviated form of the Small Litany, followed by a prayer to the Holy Trinity.

Now, at last, we are ready for the reading of God’s Word.

Part 5: Scripture Readings and the Primacy of Jesus’ Words

The deacon cries out, “Wisdom! Let us be attentive!” We listen, ready for the timeless, sacred words of the Scriptures. This section of the Liturgy begins with a reading from one of the epistles from the New Testament, followed by the Gospel.

Before the Gospel reading, the prokeimenon, which means “that which lies before,” is an expression of joyful anticipation: we sing “Alleluia” three times before hearing the words of Jesus. His words are preeminent over all others, and with our voices we proclaim our allegiance to Christ, singing “Glory to You, O Lord, glory to You!” before and after the reading. This also sets the Gospel reading apart; we don’t give the epistle reading all of this musical attention.

The reason that the Gospel passage is the final reading is because in the Liturgy of the Word, the Church has saved—as Fr. Farley writes—“the best for the last, the good wine until the end” (John 2:10; Farley, p. 39). Before the Gospel passage is chanted, the priest recites a prayer for understanding and for transformed lives as we hear Jesus’ words. (This is a wonderful prayer to use before personal Bible reading too. I have printed it at the bottom of this post.)

The priest cries out, “Wisdom! Attend! Let us hear the Holy Gospel,” and priest and laity exchange yet another blessing of peace. For those of us who worship in churches with pews, we emphasize the importance of Jesus’ words with our bodies: we remain seated during the epistle reading, but we rise for the Gospel, in the descriptive words of Fr. Farley, “like soldiers standing at attention before their commander” (p. 43).

As St. Tikhon of Zadonsk writes,

When you read the Gospels, Christ speaks to you; when you pray, you are speaking to Him. The Bible should be read not just for analysis, but as an immediate dialogue with the living Word Himself—to feed our love for Christ, to kindle our hearts with prayer and to provide us with guidance in our personal life.

The Homily

After the reading, we affirm the words of Jesus and praise God by singing “Glory to You, O Lord, glory to You!” This is the usual spot for the homily and perhaps a children’s sermon. For various scheduling reasons, some parishes include the sermon at the end of the service, but historically it goes here, after the Scriptures, a sensible inclusion in the Liturgy of the Word, this first part of the Divine Liturgy.

The homily differs from the sermons in many Protestant churches in that it is not the highlight of the service. In fact, the homily, unlike the words of Scripture themselves, is not even a mandatory part of the liturgy. Sometimes a priest might leave it out of the service because of other things going on that day in the life of the parish.

In my Protestant past, the pinnacle of Sunday morning worship was definitely the sermon. We affirmed the importance of gathering, praying, and singing together, but the greatest emphasis was on “preaching the Word.”

It’s interesting to note how human behavior reflects our understanding of the meaning of a church service. When I was part of my nondenominational church, I knew people who came late but made sure they were in time for the sermon. One man arrived on time for the service but would sit in the back and read, ignoring the worship music while others sang. But he was very attentive when the preacher stood at the pulpit and opened his Bible. Other people headed for the parking lot as soon as the service was over, with few personal relationships in the congregation.

They did this because the sermon was their destination.

Yet we’ve all seen Orthodox people who arrive at church just before communion, receive the Eucharist, then leave. Of course, all of us experience some mornings when it’s difficult to get out the door of our homes, especially with small children in tow. Not all late arrivals are intentional—on such days, we thank God that we made it to church at all. But, a significant percentage of Orthodox people skip the prayers, hymns, and the homily but make sure to receive communion.

They do this because the Eucharist is their destination.

Both approaches are wrong and out of balance. In the Orthodox Church, all parts of the service are important in order for us to prepare our hearts to approach the chalice.

So, at this point in the liturgy we have internalized the written Word with the Gospel reading and homily. If you listen closely, you’ll notice that the deacon no longer addresses the people as he did earlier. In the Great Litany at the beginning of the service, he repeated “For [the peace of the whole world, this and that], let us pray to the Lord…”. Now, in the Litany of Fervent Supplication he cries out directly to God with petitions such as, “Have mercy on us, O God, according to Your great goodness; we pray You, hearken and have mercy!” We respond with triple repetitions of “Lord have mercy,” showing a sense of urgency and expectancy.

Next we pray for catechumens, those being instructed in the Faith as they prepare for baptism. Nowadays some parishes cut out this section of the liturgy entirely. But in ancient times, inquirers required up to three years of preparation before being received into the Church. (When torture and martyrdom are real possibilities, the concept of “church membership” is not taken lightly.) The catechumens gathered for a special prayer before being dismissed from the service with, “Catechumens depart!” This command was not meant to be rude but to protect the holiness of the Mysteries. This level of secrecy is not necessary today, but the words are a small reminder of sacredness in our relentlessly secular world.

We end this fifth section of the Liturgy with an abbreviated form of the Short Litany and ascribe glory to the Holy Trinity. The Liturgy of the Word has been completed, so we will end this post in our Quick-Start Guide. Next on our journey into the Kingdom of God through the Liturgy, we will learn about sections 6 through 9 in the Liturgy of the Faithful, or Liturgy of the Eucharist, the second part of the service.

But before we continue our ascent to the Eucharist, we’ll pause and take a look around at those who are journeying with us. As I said before, we are not on a solo hike—we ascend the spiritual path along with other pilgrims.

Next time, we’ll consider our traveling companions, seen and unseen. I hope you can join me.

***

Prayer Before Reading God’s Word

Illumine our hearts, O Master who loves mankind, with the pure light of your divine knowledge. Open the eyes of our mind to the understanding of your gospel teachings. Implant also in us the fear of Your blessed commandments, that trampling down all carnal desires, we may enter upon a spiritual manner of living, both thinking and doing such things as are well pleasing unto You.

For You are the illumination of our souls and bodies, O Christ our God, and unto You do we ascribe glory, together with Your Father, who is from everlasting, and Your all-holy, good, and life-creating Spirit, now and ever and unto ages of ages. Amen.

***

You can find this prayer and others in a free app (icon above) called the “Pray Always” Orthodox Christian Prayer Book, available in the App Store for iPhones and on Google Play for Android phones.

Again, insightfully inspired. Thanks!

Thank you, Gordon!

A very nice summary and commentary, though in a couple of places you ascribe to the priest words or actions done by the deacon.

Thank you, Dn. Nicholas. You are correct! But I’ve attended many services where no deacon was in attendance, although two priests were; and some of the “scripts” in various books use “priest.” I could write “clergy” each time, but that gets a bit awkward. I’ll try to be more precise. 🙂