[This is a greatly expanded version of a post from three years ago. – LH]

We’re about a week and a half into Great Lent, and as far as I can tell, the Orthodox faithful are still standing. And prostrating.

If you are able, physically and medically, to follow the full Lenten fast, you should be getting a bit cranky about now. Your body and your emotions are craving your favorite foods, and you’re aware of your weakness. You know this is a good thing, to be reminded of your dependence on God and of your struggle with saying “no” to yourself. But it sure doesn’t feel good.

In our last episode I talked about anticipating Great Lent, looking forward to change and spiritual readjustment. But most years, I tend to view the Mother of All Fasts with both anticipation and dread: Anticipation of the sweetness of walking this journey with my brothers and sisters in Christ, and dread because . . . Well, dang, Lent just goes on and on.

Throughout the year, most Orthodox fasting periods are short, and fasting days follow an essentially vegan diet—no meat or dairy, although shellfish is permissible. It’s doable.

And then . . . Great Lent arrives. (Cue the scary violins from Psycho.) It means going vegan for forty days (with extra treats allowed here and there), followed by seven more days of fasting during Holy Week.

But wait, there’s more! The Church also jump-starts the season with a vegetarian week beforehand. (Perhaps the holy Fathers longed for one last fling with the mac and cheese too.) So we’re talking fifty-six days of dietary restriction. Plus longer daily Bible readings and lots of extra services to attend.

No other Christian tradition is so rigorous. (Or, more accurately, the other traditions have eased up on the guidelines of historic Christianity or jettisoned them entirely.) I once saw the following bumper sticker on the back of a sedan:

I laughed—a little uncomfortably. Because a faithful Catholic or Protestant believer might ask, Aren’t all those requirements legalistic?

It’s a good question. The honest answer is that any discipline can become an empty rule if we neglect the heart behind it.

Still, nothing in my past prepared me for Orthodox lenten practices, even when approached with a humble, Christ-centered outlook. My Evangelical background valued individual religious experience in spiritual formation. Some of the churches I attended ignored Lent altogether, and Holy Week was really more of a Holy Weekend, with Good Friday, a Saturday lull, then Easter. (Some churches earned extra credit by hosting beautiful, meditative Maundy Thursday services.)

Why Do We Fast?

In his helpful, short and sweet book Toolkit for Spiritual Growth, Fr. Evan Armatas points out that God’s first commandment in the Garden of Eden is a command to fast: “But from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil you may not eat; for in whatever day you eat from it, you shall die by death” (Gen. 2:17). After His baptism, Jesus also fasted for forty days before beginning His public ministry. As Fr. Evan writes, “The fast puts the body and soul back into a right relationship” (p. 71). He continues,

Our physical nature is important in our relationship with God. Fasting from food and not being a slave to our appetites are disciplines that should not—or cannot—be ignored in our spiritual development. If people believe they can simply grow without fasting and that their spiritual selves are wholly independent from their physical bodies, they are, quite literally, trusting in a philosophy that even the Lord Jesus Christ Himself did not adhere to. (pp. 106-107)

And our longest fast, Great Lent, is “a period of self-examination and evaluation in which fasting is not an end in itself, but rather a means toward a greater goal, the Kingdom of God” (p. 92).

Few parishioners can attend every Orthodox service offered during Lent. We do what we can, and we reap sometimes unexpected spiritual benefits. The ancient, traditional approach to fasting that the historic Church has followed for almost two millennia has taught me five powerful lessons:

1. Fasting is not a private matter between God and me.

During my years as a committed Protestant Christian, fasting was taught and practiced as an individualistic activity. People fast when they “feel” the need, usually when seeking direction from God or specific answers to prayer. I remember fasting when I was facing a difficult situation or needed to make an important decision.

This is a good idea, but I would do it differently now as an Orthodox Christian. More on that in a moment.

Sometimes groups, like the missions committee or the elders, would fast together. Sometimes an entire congregation would fast. But there were no fasting seasons, and no consistent direction, time-tested through history.

In contrast, the Church in her wisdom offers guidelines and has promoted fasting over 2,000 years, from the Israelites in the Old Testament, through Jesus’ example and teachings, and on through the apostles and those who came after them.

The Didache, written around AD 150, describes Christians fasting on Wednesdays, when Jesus was betrayed, and on Fridays, when He was crucified. The Orthodox Church has continued this practice throughout the millenia. Jewish people evidently fasted on Mondays and Thursdays, and chapter 8 of the Didache says, “But let not your fasts be with the hypocrites, for they fast on the second and fifth day of the week [Monday and Thursday]. Rather, fast on the fourth day [Wednesday] and the Preparation (Friday).”

The modern, individualistic approach to fasting can be problematic. There are dangers to going it alone. It’s easy for an attitude of spiritual superiority over the non-fasting masses to take root. The personal approach also can lead to self-deception: an implicit belief that any idea that comes to me must be a specific word from God as a result of my fasting, and with His seal of approval, I don’t need any other counsel.

The Church addresses this tendency before Great Lent begins by devoting a Sunday service to the Parable of the Publican and the Pharisee. Note that in prayer, the Pharisee sees himself as better than others and informs God, “I fast twice a week; I give tithes of all that I possess” (Luke 18:12). Prayer, fasting, and almsgiving—he’s doing all the right things, for all the wrong reasons. The sinner who repents is the one who is acceptable to Jesus.

Also, when we go it alone, our inner pendulum can swing to the opposite extreme: we set lofty goals for ourselves, then when we inevitably crash and burn, we can be filled with self-loathing and self-condemnation. The Church deals with this tendency on the following Sunday of the Prodigal Son. The son, in his failure and rebellion, cannot imagine that his father would receive him back to his home, but the father runs to him and embraces him as he confesses his sins. Returning to God is always an option, and the one that our heavenly Father longs for.

When we fast together during the Church’s fasting days and seasons, the fasting is about us, seeking God individually but also in community. The fasting days have nothing to do with my feelings or the Spirit speaking specifically to me (and, by extension, not to you). Fasting is about the need we all have to curb the desires of the flesh and to seek God together in unity.

2. Fasting requires submission to spiritual authority.

This is related to the admonition not to go our own way in our Lenten practices. Orthodox Christians should approach fasting with the guidance of a spiritual father, usually the parish priest. He can suggest modifications to the fast because of dietary restrictions, medical issues, and spiritual needs. This is where the corporate becomes personal, and the timeless wisdom of the Church is applied to individuals with grace instead of legalism. Valuing a priest’s wisdom and submitting to his authority also helps guard against both spiritual pride in our efforts and the sense of failure that can result from overzealous striving.

The measure of a man’s spiritual growth is his humility. The more advanced he is spiritually, the more humble he is. And vice versa: the more humble, the higher spiritually. Neither prayer rules, nor prostrations, nor fasts, nor reading God’s Word—only humility brings a man closer to God. Without humility, even the greatest spiritual feats are not only useless but can altogether destroy a person. — Abbot Nikon Vorobiev, Abbot Nikon: Letters to Spiritual Children, p.141

Some of us have food allergies; others have medical conditions, such as diabetes or heart disease, that require specific diets. Our normal, do-it-yourself tendency is to self-prescribe and figure out an approach to fasting on our own.

Father Evan writes,

The Church understands this reality and works with individuals to understand their place in this struggle. But, again, this is why I stress the importance of having a spiritual father. These concepts cannot be regularly self-applied—they should come through the pastoral office. The Church, through love, looks at the circumstances of the person and modifies what is necessary. (p. 105)

So, whether you are new to fasting or have been following the Church’s prescriptions your whole life, make an appointment with your priest. He will look at your circumstances and keep you from taking on too much . . . or too little.

On his call-in show Orthodoxy Live, Fr. Evan gave a personal example from his seminary days. He was talking to his father confessor and mentioned an extra form of ascesis that he had taken on for Lent. His confessor was not impressed and told him that during the Lenten fast, Fr. Evan was to eat meat. Not only that, he was to eat meat in front of his fellow seminarians. And he was not to tell them why.

This wise priest saw pride and self-will arising in the young student named Evan, and he made sure to cut them off at the roots. I’m confident that Fr. Evan learned some powerful lessons from the experience, and one of them was the importance of not going it alone.

The story makes me laugh, mostly because it didn’t happen to me.

I wrote earlier that I would approach personal fasting differently now than I did in my past. The difference is that I would ask for my priest’s guidance and counsel. If I am taking on extra fasting to seek an answer to prayer, he might be able to see things in me that I can’t see—hidden motivations, false guilt, or maybe a desire to manipulate God.

I don’t want to journey alone, ever again.

3. Fasting is not about personal preference.

This seemed really weird to me at first. As I wrote earlier, I was accustomed to a variety of fasting practices. People set their own dietary rules—strict water fast, liquids-only fast, skipping one meal a day, and giving up chocolate or television. Fasting involved just me and Jesus, doing our thing.

But in Orthodoxy, we’re all on this journey together. Nobody has to make up the rules of their own personal fast, because the Church has laid out the path for us in terms of the schedule and dietary requirements. We don’t determine what to give up, or when. Instead, we humble ourselves and walk this path as a Body, setting aside self-will and trusting God to work in us through His Church.

Let us fast in a way that is acceptable and pleasing to the Lord. True fasting is flight from evils, temperance of the tongue, refraining from anger, separation from lustful desires, and from lies, from falsehood and from perjury. The absence of all these makes our fasting true and acceptable. — Vespers Service, Clean Monday

In a helpful Q&A on the website of the Orthodox Church in America, a priest explains,

The purpose of fasting is not to “give up” things, nor to do something “sacrificial.” The purpose of fasting is to learn discipline, to gain control of those things that are indeed within our control but that we so often allow to control us. In our culture especially, food dominates the lives of many people. We collect cookbooks. We have an entire TV network devoted to food [the “Food Channel”]. We have eating disorders, diets galore, weight loss pills, liposuction treatments, stomach stapling—all sorts of things that proceed out of the fact that we often allow food, which in and of itself cannot possibly control us, to control us. We fast in order to gain control, to discipline ourselves, to gain control of those things that we have allowed to get out of control. Giving up candy—unless one is controlled by candy—is not fasting. It is giving up candy, or it is done with the idea that we fast in order to suffer. . . .

But suffering is not the goal, which leads to lesson #4:

4. Fasting is not about suffering.

In the OCA article, the author continues,

. . . But we do not fast in order to suffer. We fast in order to get a grip on our lives and to regain control of those things that have gotten out of control. Further, as we sing during the first week of Great Lent, “while fasting from food, let us also fast from our passions.”

Our soul and bodies are integrated: the fast affects the body, and the body affects the soul. Father Evan writes,

The fast puts the body and soul back into a right relationship. What we do with our bodies affects our spiritual selves, as they are inherently connected. We are not ghosts in a machine! . . . Fasting builds our spiritual muscles so we become able to conquer the tougher passions. (p. 71)

A priest may counsel a parishioner to fast in order to address struggles with anger or lust. Few of us are strong enough to conquer ingrained, sinful habits head-on; we gain spiritual strength through the self-denial of fasting, and with God’s help we are strengthened to say “no” to ourselves in other areas.

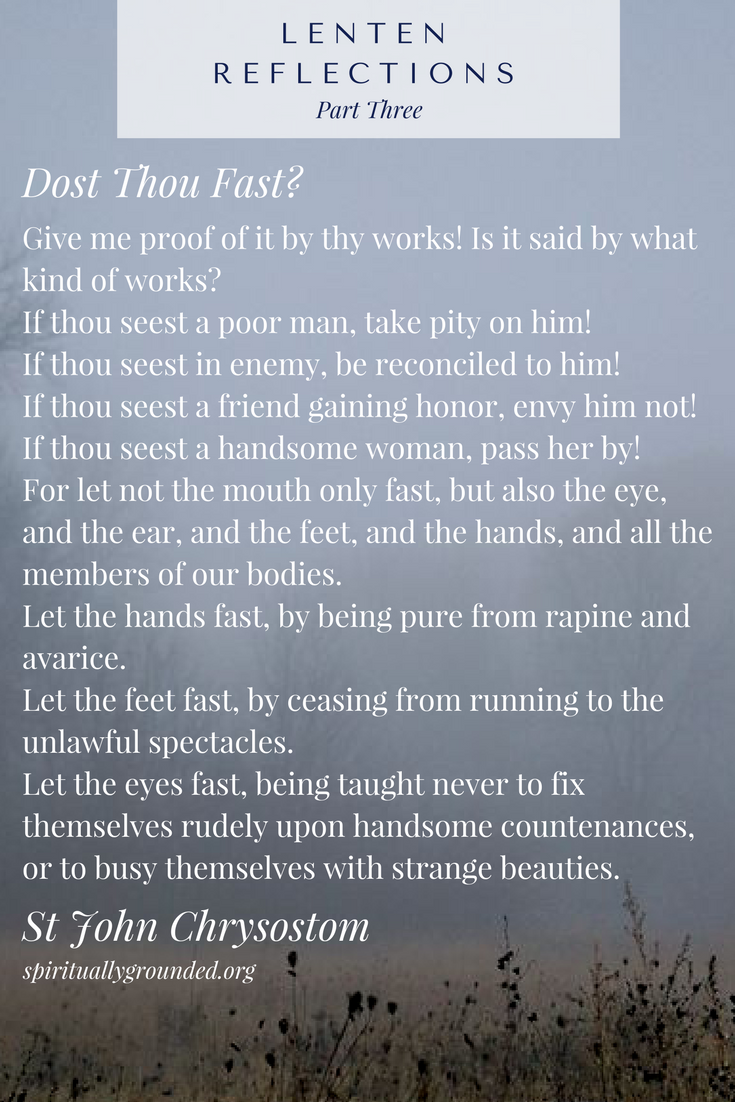

Fasting is wonderful, because it tramples our sins like a dirty weed, while it cultivates and raises truth like a flower. — St. John Chrysostom

In other words, fasting is about freedom. By using God-given tools—notice that in Matthew 6:16-17 Jesus said “when you fast,” not “if you fast”—we can begin to conquer our passions.

I’m still working on truly understanding the most powerful lesson:

5. Fasting is not ultimately about food.

A wonderful saying states, “Fasting without prayer and almsgiving is dieting.” If I abstain from certain foods without devoting extra time to prayer—time that has been freed up from planning and preparing fancy meals—I am simply following a food plan.

If I abstain from certain foods without donating extra money—money that I’ve saved by not buying expensive meats and cheeses—I am simply giving up things without truly cultivating a spirit of giving in my life.

If I abstain from certain foods with feelings of resentment or with the hope of “bribing” God for His favor, I should probably grab a Big Mac for lunch and call it a day. Or better yet, call my priest to set up an appointment for an attitude check.

Beware of measuring fasting by abstaining from food. Those who abstain from food but behave badly are likened to a devil who, although he does not eat anything, doesn’t stop sinning. — St. Basil the Great

We do not fast to prove ourselves or to cling to outdated rules. We fast to remind ourselves to exercise self-control in so many other areas of our lives.

We fast to grow in our relationship with Christ, which results in growing in love toward God and our neighbor.

St. John Cassian wrote,

Fasts and vigils, the study of Scripture, renouncing possessions and everything worldly are not in themselves perfection, as we have said; they are its tools. For perfection is not to be found in them; it is acquired through them. It is useless, therefore, to boast of our fasting, vigils, poverty, and reading of Scripture when we have not achieved the love of God and our fellow men. Whoever has achieved love has God within himself and his intellect is always with God.

Saint John Chrysostom, the great fourth-century preacher and the author of the Divine Liturgy used most frequently in the Orthodox Church, said it best:

The joy of Pascha is fast approaching. (Pun intended.) We’re on our way. May God grant continued good strength to us all!